Comprehensive History

1704-1770

1704-1770

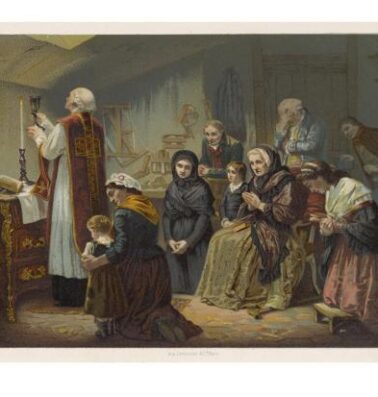

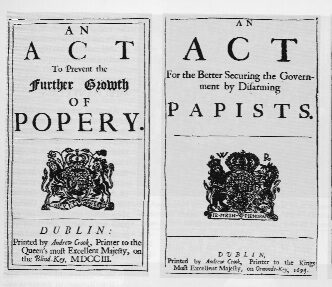

The Priests of Faughanvale and Glendermott were outcast from their positions as religious leaders. In 1704, there were only 26 Diocesan Priests in the Derry Diocese, with a priest jailed for ministering outside of his Parish.

What happened in Glendermott during these bitter years will never be known. Documentary evidence either did not survive or was not produced.

We are forced back on oral tradition, something that must always be received with the greatest caution, because, in addition to the danger of an initial inaccurate observation, such evidence necessarily passes through so many channels that one has to check it at every stage. Many traditions of the parish that survive today were written down in 1905 by Father McKeefry, a painstaking chronicler, and some stories told to him came down in a single family, whose great-grandfather had been an eye-witness of the event in the mid-eighteenth century. When the channel is as direct and as brief as this, one should be able to use the information safely.

There is constant reference to Mass having been said in the Oak Wood or more properly, the Birch Wood, at Ardmore. The Ordinance Survey Memoir mentioned the altar as still surviving at 1837, but gives no indication of its age. ‘Ardmore altar properly speaking is a wall about 8 feet long, with a projecting table of loose stones, and two flags forming the steps. On one occasion, the celebrant, Father McKinney, found himself with twelve of a congregation, and took the opportunity of questioning them in the catechism. It is said that only one of those present, a man named Logue, was able to answer. Religion had fallen so low in the district, that people were not only afraid but ashamed to be known as Catholics. The wood is supposed to have had its martyr too. The story is that a man came out from the trees, his clothes covered with blood, and boasted to a passer-by: “I am after doingaway with one of the black game”.

Fincairn Glen was another recognised place for public mass. The ordinance survey reports, ‘the altar was an accidental stone, selected by the priest, as well adapted for his purpose.

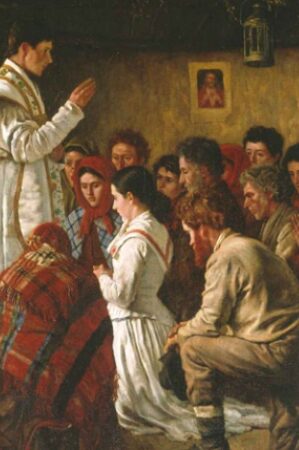

There is also evidence that protestants were not at one in their hostility to Catholicism and that certain families contributed considerably to keeping the faith alive. The Knox’s of Prehen always had Catholic servants and it is said Watsons of Glenkeen kept a Priest for years disguised as a herd, concealing him in the cellar of their home in times of danger. Such deeds shine out like a torch in darkness.

An occasional visit from a priest, a handful at Mass, uneducated peasants deprived of the Sacraments and biting poverty characterised the parish for the first half of the eighteenth century. Perhaps their very misery saved these Catholics, they were so poor that they were hardly worth persecuting. The courage of the priests, their acceptance of hardship and risk seems to have fired the imagination of the people, arousing them in a spirit of religion that nothing could subdue. By 1750, the battle had been won, but the Faith had survived and never again could anyone unleash persecution as in the past.

The priest in charge of Glendermott was Fr McEvlar in 1766 with 386 Catholic families in Glendermott and over 884 in Faughanvale, well over 2,000 souls. He dwelt at the Cross (Cross Baile Cormaic) and said Mass at the Sand Hole. On Good Fridays the people were accustomed to assembling, with the main feature being a sermon on the Sacred Passion. The fact a crowd could meet without fear and molestation was indicative of the new situation. Fr McElvar was probably a native of the parish. When one considers that he had no Church, that his only means of transport was horse, and that most of the roads were little better than tracks, one realises what difficulties he worked under.

(Coulter,1958)

1774-1794

The Penal code was relaxed with Catholics able to testify their allegiance and further concessions were made conditional on taking the oath. Whilst Catholics were initially reluctant to swear the oath, Catholics of all degrees hastened to swear following lead by the Bishops.

James McFeely, Pastor of Fohanveal and Glendermott subscribed to the oath in 1782, the same year in which the Relief Act, which repealed most of the penalties decreed against ecclesiastics was passed. The law now tolerated that a Priest could publicly perform the Rites of the Church, but not in a building with steeple and bell. Fr McFeely, from McFeely’s Height in Glenkeen, built the first church in Glendermott, with the chapel at Ardmore completed by 1791. The Chapel at Ardmore, in Currynieran townland was almost certainly erected by direct labour of the parishioners. Poor it was, had significance far beyond its size, for it marked the end of an epoch, and the beginning of a new age for Catholicism in the district. Fr McFeely was transferred to Cumber in 1794.

(Coulter,1958)

1798

Whilst the 1798 rebellion had only slight repercussions in the parish, relations in Derry between both denominations had became cordial, due to Anglican Bishop of Derry Hervey Bruce, unremitting in his endeavours to secure concessions for Catholics, demonstrating his friendship on many occasions. With the Church throwing its weight against the United Irishmen, tradition insists there were disturbances with shootings and house burnings. However, Catholics held aloof and escaped the savageries that occurred elsewhere. (Coulter,1958)